When progress stopped being generational and became personal

For most of human history, innovation moved slower than memory.

A farmer born in 1200 would die in a world recognizable to his grandparents. Roads were the same roads. Ships were the same ships. War, trade, and distance obeyed identical physics for centuries. Change existed — but it belonged to historians, not to individuals.

Then, suddenly, the twentieth century compressed time.

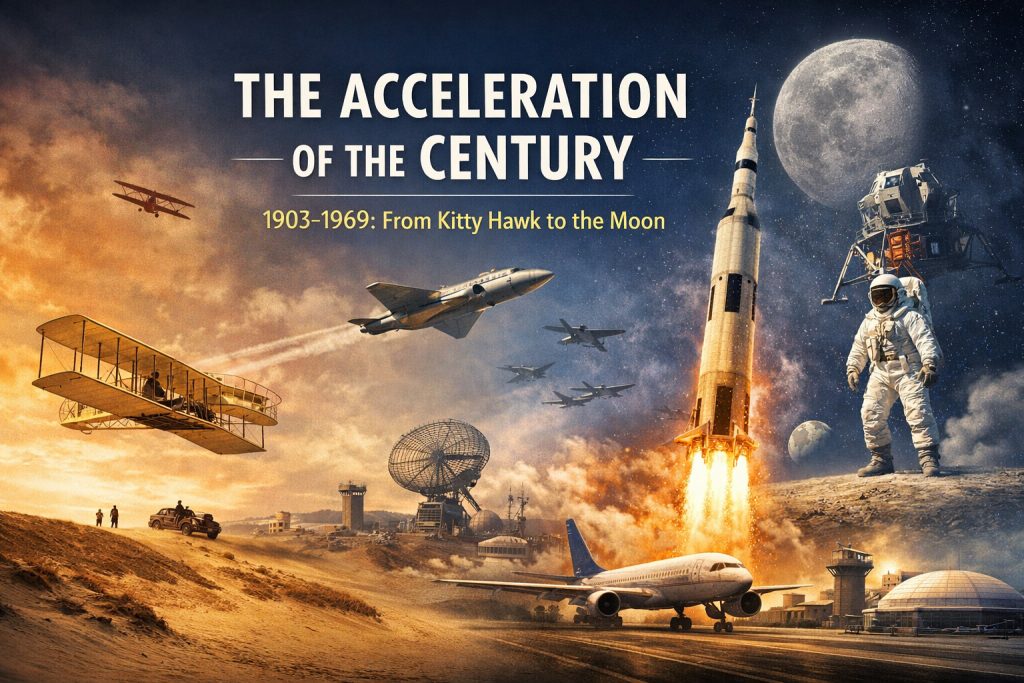

Between 1903 and 1969, humanity didn’t just improve technology.

It changed the scale at which reality operates.

A person born before powered flight could retire after watching humans walk on another world.

Civilization shifted from evolutionary to explosive.

1. Speed Became a Human Property

Before the airplane, speed belonged to nature.

Wind. Rivers. Horses. Steam.

Humans endured movement — we didn’t command it. Even the fastest train still chained you to geography. Oceans remained psychological barriers. Continents felt permanent.

Then powered flight arrived, and something subtle happened:

velocity detached from terrain.

Distance stopped being measured in effort and started being measured in planning.

The world didn’t shrink physically.

It shrank cognitively.

A place you can reach in a day is no longer foreign — it becomes part of your mental neighborhood.

2. War Turned the Sky Into Infrastructure

Conflict accelerated innovation more brutally than curiosity ever could.

Within four decades humanity went from fabric wings to jet engines. Not gradually — urgently. Survival demanded it. Nations industrialized physics itself.

Navigation, radar, pressurized cabins, global logistics networks — these were not designed for tourism, yet they made tourism inevitable.

By mid-century, the sky stopped being an obstacle and became a highway.

Airspace replaced coastline as the true geography of the planet.

3. The Sound Barrier Was Psychological

Breaking the sound barrier was not only an engineering milestone.

It was philosophical.

For centuries people believed nature imposed absolute limits — speeds, heights, distances that simply belonged to gods or imagination. When humans exceeded Mach 1, it wasn’t just faster travel.

It was the first clear evidence that “impossible” might only mean “temporarily unexplained.”

After that, the Moon was no longer fantasy.

Only scheduling.

4. The First Time Humans Left the Earth

When a human first entered orbit, humanity crossed a line evolution never prepared us for: we observed our habitat from outside it.

Every previous civilization experienced the sky as a ceiling.

Now it became a viewpoint.

From orbit, borders vanished. Weather revealed structure. Continents became patterns rather than territories.

The greatest cultural shift of the century wasn’t technological — it was perceptual.

Earth stopped being the world.

It became an object inside the world.

5. Why This Period Was Unique

Technological progress still continues, but its character changed after the Moon landing.

Today innovation improves experience.

That era changed existence.

- Faster planes improved travel time

- Orbit changed perspective

- The Moon changed human identity

The acceleration of the century was not about machines becoming better — it was about humans discovering they were not confined to their evolutionary environment.

For the first time since walking upright, our species updated its definition of “where life can happen.”

A Quiet Consequence

We now live in the aftershock.

Modern travelers complain about delays measured in minutes while crossing distances kings couldn’t cross in a lifetime. Airports feel ordinary precisely because they represent the completed revolution.

The extraordinary always becomes infrastructure.

But the deeper transformation remains invisible:

human beings are psychologically a spacefaring species trapped in a routine phase.

The early twentieth century did not just invent aviation.

It altered expectation.

Before 1903, progress meant improvement.

After 1969, progress meant transcendence.

And ever since, every generation has lived with a subtle belief inherited from that brief era:

That the next impossible thing might happen within our own lifetime.

Maarten’s Note

As someone who checks flight paths before breakfast and still instinctively looks up whenever a distant engine crosses the sky, I sometimes forget how unnatural aviation really is.

For us — frequent flyers, seat-map analysts, airport wanderers — flying feels procedural. A boarding group, a safety card, a routine climb to 11 km. Another Tuesday somewhere above Europe.

But the “Acceleration of the Century” reframes it completely.

A human born in 1900 would have spent childhood in a horse-speed world… and middle age watching live images from the Moon. Not science fiction — scheduled programming. Imagine explaining that to someone standing beside the Wright Flyer:

“Within your lifetime, people will complain about legroom while traveling faster than sound used to travel.”

We live after the miracle, which makes it invisible.

Every contrail is evidence that humanity once solved the biggest problem it ever faced — not distance, but gravity — and then normalized it so thoroughly that we now judge airlines on sandwich quality.

Sometimes while cruising at night, somewhere between cities that used to require months to connect, I try to remember that we are not experiencing advanced transportation.

We are experiencing the quiet continuation of the most radical 66 years our species ever lived.

And the strangest part?

We still treat it as ordinary.

Leave a Reply